Bill Plympton

An Artist & Film Deep Dive

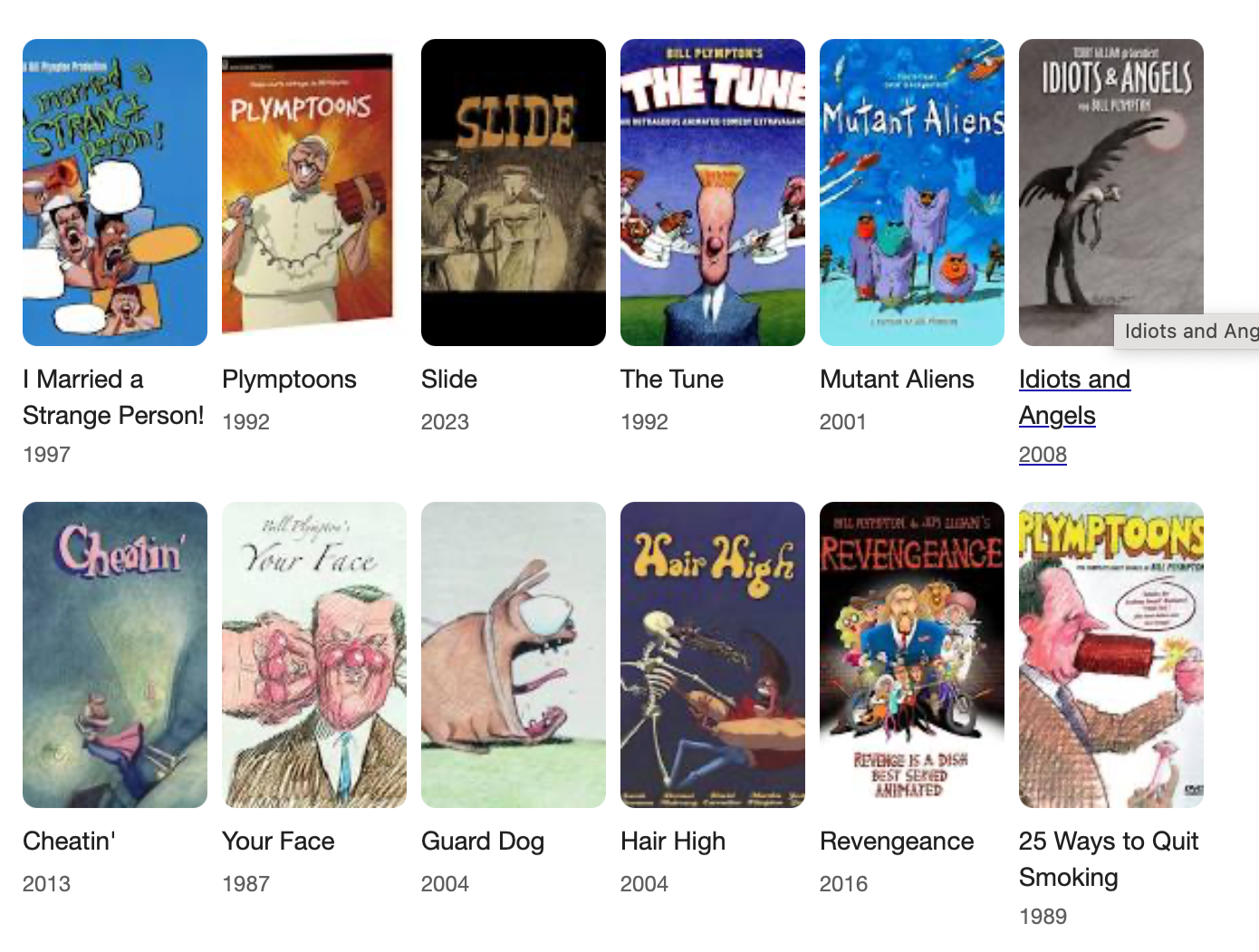

Image: Screenshot of Google search results displaying selected works by Bill Plympton.

Works © Bill Plympton. Screenshot captured via Google Search, accessed January 2026.

DropDate: December 31rst 2024

Bill Plympton was born in Portland, Oregon, a place he has often credited—half seriously, half playfully—with shaping his imagination. Growing up in the rain-soaked Pacific Northwest in the 1950s, Plympton developed an early attachment to drawing, color, and movement. There is something fitting about that origin: his work has always felt weathered, restless, and alive, as though it emerged from an environment that encouraged introspection and experimentation rather than polish.

I first encountered Plympton’s work by accident. The television was on, and suddenly those strange, unmistakable animations appeared—odd, elastic, and impossible to ignore. I didn’t know who made them at the time, only that I wanted more. Eventually, that curiosity led me to Cheatin’, a film that lingered long after the screen went dark, stuck in my mind like a song you can’t shake. It was obsessive, romantic, grotesque, and tender all at once. And, fittingly, it was about love.

Plympton’s career has always existed slightly outside the mainstream, even when brushing up against it. In 1991, he won the Prix Spécial du Jury at the Cannes Film Festival for Push Comes to Shove, which later aired on MTV’s Liquid Television, a platform that introduced many viewers to experimental animation in the early 1990s. The following year, his first feature-length animated film, The Tune, debuted at the Sundance Film Festival. Remarkably, the film was almost entirely hand-drawn by Plympton himself—a feat that would become central to his reputation.

Before feature films, Plympton worked as a cartoonist for publications such as The New York Times, The New Yorker, National Lampoon, Playboy, and Screw. This background in editorial illustration shaped his sensibility: concise, confrontational, and unafraid of discomfort. His drawings never aim for prettiness. Instead, they stretch, distort, and exaggerate the human body into something unstable, emotional, and often absurd.

What distinguishes Plympton is not just his aesthetic, but his commitment to independence. He has built a career by working almost entirely outside studio systems, often animating feature films largely on his own. This approach earned him the informal title of the “godfather of indie animation,” not because his work is universally accessible, but because it insists on artistic autonomy at a scale few have attempted.

That independence is especially evident in Cheatin’ (2013), a feature film partially funded through Kickstarter. The film tells the story of two lovers, Jake and Ella, whose intense devotion mutates into jealousy, paranoia, and violence. Inspired in part by the writing of James M. Cain and Plympton’s own experiences, Cheatin’ explores how love and destruction can coexist within the same emotional space. The animation is fluid and unrestrained, visually mirroring the instability of the relationship it depicts.

Plympton’s work has also intersected with popular culture in unexpected ways. In 2005, he was contacted to animate a segment for Kanye West’s “Heard ’Em Say,” featuring Adam Levine, completing the work in a matter of days. Later, he illustrated Through the Wire: Lyrics & Illuminations (2009), a graphic memoir interpreting West’s lyrics through animation and illustration, a project supported by West’s mother, Donda. While these collaborations brought his work to new audiences, they never diluted his distinctive style.

Visually, Plympton’s animation is unmistakable. His figures are exaggerated, stretchy, and often grotesque, rendered through a pencil-on-paper technique that gives each frame a shaky, breathing quality. Violence and sexuality appear frequently, not for shock alone, but as extensions of emotional extremes. His films are funny, uncomfortable, and strangely intimate, operating on a logic closer to dreams—or nightmares—than traditional narrative animation.

Beyond his films, Plympton has continued to teach and share his process through what many fans refer to informally as “The Bill Plympton School of Animation,” a philosophy more than an institution. Through talks, workshops, and online platforms, he offers insight into independent production, reinforcing the idea that animation does not require massive infrastructure—only persistence, discipline, and a willingness to draw relentlessly.

Bill Plympton’s influence is quiet but profound. He has demonstrated that feature-length animation can be created outside studios, outside trends, and outside expectation. His films do not ask to be liked universally. They ask to be experienced honestly. In doing so, Plympton has carved out a body of work that remains singular, uncompromising, and deeply personal—proof that independence itself can be an artistic medium.

Sources & Further Viewing

Plymptoons Official Website

Plymptoons Store (Cheatin’ Blu-ray)

Plymptoons Patreon

Cannes Film Festival archives (Push Comes to Shove)

Sundance Film Festival archives (The Tune)